The Nigerian government has now suspended its proposed 15 percent ad valorem tariff on imported petrol and diesel, pending further review and stakeholder consultations. This comes after intense public debate over the policy’s likely broad impacts and timing. With tensions down, perhaps it makes sense to objectively examine some of the data, the issues and risks central to the continuing discourse on downstream petroleum reform.

Policy intent: Protecting local refiners and saving forex

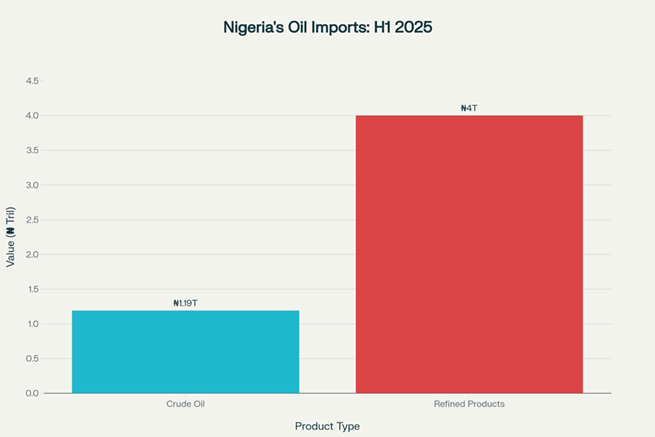

The administration initially presented the tariff as a strategic measure to stimulate investment in local refining, reduce reliance on volatile world markets, and save foreign exchange. With the Dangote Refinery and several modular refineries already in production, and another major $5 billion refinery potentially in development, officials argued that shielding domestic refiners from cheaper imports would foster competition, self-sufficiency, and job creation. However, striking a balance between local production and import dependence for refined products remains essential—especially as Nigeria’s energy import bill is still dominated by refined products and not crude oil, as Chart 1 shows. Evidently, the pathway to saving forex lies in reducing dependency on both crude and refined petroleum imports, and the key to boosting forex earnings is to produce and export more of both, with enough local usage to keep the economy humming.

Chart 1: Nigeria’s crude oil vs. refined products import value, 1st half 2025

Import realities: Market exposure and volatility

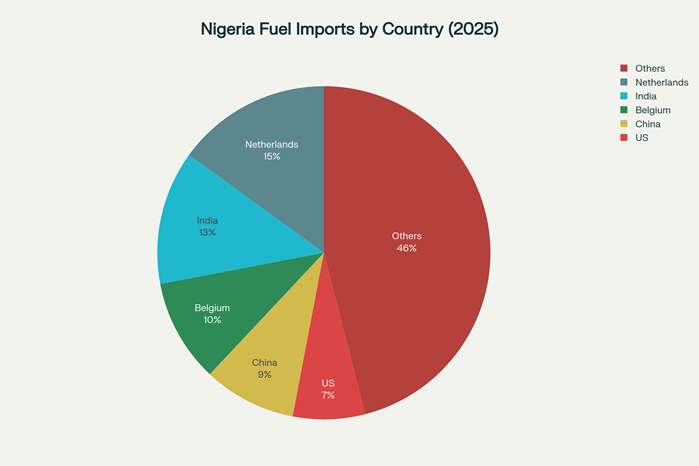

Despite the positive framing of this policy’s objectives, the evidence reveals a more complex reality that needs careful consideration. Nigeria’s refined product imports in H1 2025 reached ₦4 trillion, more than triple crude oil imports of ₦1.19 trillion. As Chart 2 highlights, some of Nigeria’s major suppliers of refined products—such as India, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the US—are also among the most significant buyers of Nigeria’s crude oil, reflecting deep integration into global energy value chains.

Any disruption, whether caused by tariffs or other market shifts, can rapidly impact sensitive supply and price structures, often connected to national energy security, beyond just trade and fiscal policies. For instance, what might become of Nigeria’s crude oil market competitiveness if these same countries imposed tariffs on Nigeria’s crude oil exports to them, as it often happens, whether in retaliation or to protect their own economies?

Chart 2: Nigeria’s refined fuel imports split by country of origin, 2025 (%)

Note: Nigeria’s major refined product suppliers, such as India, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the US, are also some of the most important buyers of Nigeria’s crude oil.

The wide distribution of product origins underlines Nigeria’s linkages with international refined product markets and supply forces, making the sudden rise in pump prices—now hovering near ₦1,000/litre—inevitable. Reactions by many commentators and stakeholder groups as soon as the policy was announced indicate that a price spike, flagged by business groups and labour unions, was highly likely. Sadly, some fuel stations and transporters had already adjusted prices before the regulator suspended the tariff at the last minute.

Such fuel price spikes tend to erode the competitiveness of the Nigerian industry, spark inflation, and undermine government efforts toward inclusive economic reform. In fact, it ultimately shrinks Nigeria’s export and forex earnings, partly by making refined products and crude oil produced in Nigeria more expensive than those imported from elsewhere. This leads to a vicious cycle of more rather than fewer imports of both.

It’s worth noting that Nigeria currently has the highest production cost for crude oil and refined petrol (about $27.5 per barrel and $0.63 per liter) among fellow African members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, OPEC. Nigeria is even more of an uncompetitive producer and exporter when you compare it with bigger non-African exporters in and out of OPEC, such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the US and others, who play in the same interconnected global energy market. Among the big reasons for this unenviable position are policy inconsistency and fiscal duplication, compounding structural challenges, cost and lack of capital, insecurity and the like.

It is also important to consider that Dangote, and potentially other local refiners, export refined products to other countries. If these buyers impose tariffs on products imported from Nigerian refineries, local producers could suffer. Nigeria also relies on many of these countries for inputs and capital in sectors such as oil and gas, manufacturing, and agriculture, further underlining the complex consequences of trade policies.

Read also: Government 15% fuel import tariff: Boost for local refining or burden on Nigerians

Social impact: Inflation, inequality, and public risk

Sound energy policies usually consider not just immediate macroeconomic outcomes but also the longer-term socioeconomic impacts at the ground level. For a country like Nigeria, whose economy is so closely linked to oil, evaluating the street-level consequences of such a policy is crucial. Civil society and industry opinion leaders, not just marketers, have argued that the now-suspended tariff was proposed at the worst possible time. With households already struggling from subsidy removal, food inflation, and recent currency instability, further cost escalation risks pushing millions deeper into poverty and some into desperation. There were strong concerns that a tariff, absent complementary policies, may entrench long-term social and economic disparities and damage trust in government.

Global tariff lessons recommend caution

Recent global trade tensions show that commodity tariffs often provoke unpredictable consequences: sparking retaliatory barriers, feeding black markets, amplifying inflation, triggering market disruptions and large layoffs, and ultimately stifling inclusive growth. Can Nigeria afford to join the fray of global tariffs? What does our balance of trade say about our strengths and vulnerabilities? With foreign reserves barely enough to cover even our foreign debt, to say nothing of our still-growing domestic obligations, Nigeria must proceed with caution. It’s worth paying attention to the lessons from the US-China trade standoff and recent European energy policy rethinks, and the struggles of countries like India and South Africa with juggling energy, fiscal and industrial policies in an era of global trade protectionism and volatility.

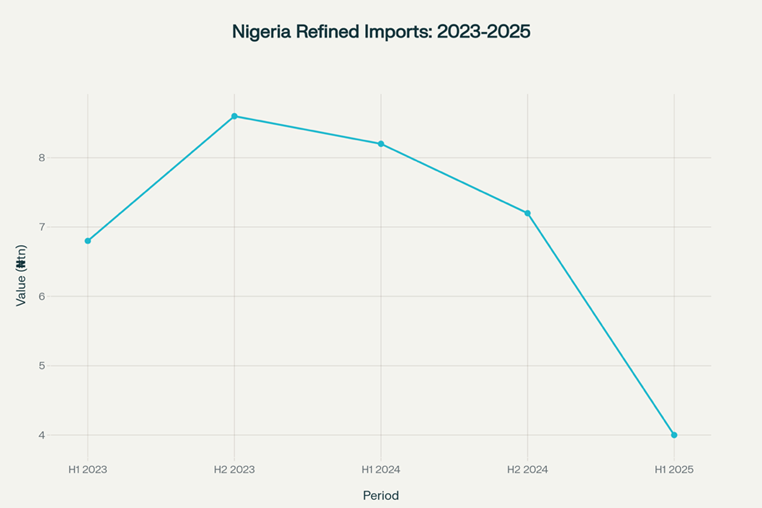

Trends show diminishing imports, shifting risks

Nigeria’s refined fuel import bill has drastically decreased, as can be seen in Chart 3, thanks to output from the Dangote refinery, other private refineries, and intermittently operational NNPC refineries. No question, these outcomes are positive and worth sustaining with deliberate follow-on policies.

Yet, imports have not disappeared altogether, nor should achieving zero imports be an absolute priority by itself. Time has proven that the most robust energy policies promote diversification and market dynamism. Openness and flexibility should remain the goal, given continued price, supply, and geopolitical risks — at least until local refining meets most domestic demand sustainably. And that takes a suite of policies working together in synch, not blunt-edged tools such as hurried tariffs tend to be.

Chart 3: Half-yearly value of Nigeria’s refined product imports, 2023–2025 (₦ trillion)

How to support local refineries

Among the many challenges facing local refiners, competition from imported products is often far down the list. Refiners most often cite a lack of crude oil feedstock from local producers as their chief problem. Nigeria’s energy policy has sought to address this by mandating a domestic supply obligation (DSO) for crude producers. Yet, large refiners like Dangote still import heavy volumes of crude with hard currency, indicating that the DSO policy has not fully succeeded and needs reinforcement instead of further disruption. Focusing on strengthening local crude production will yield more sustainable benefits than targeting imports alone.

Recommendations for a sensible path forward:

• With the tariff now suspended, the government should use the time to analyse market complexities and only consider reintroducing it when local supply can meet at least half the demand. Even then, the implementation needs to be carefully sequenced and calibrated to sensitive economic factors.

• During this period of recalibration, the government should engage more extensively with local and global stakeholders, especially key refined product exporters who are also major buyers of Nigerian crude oil, to avoid potentially costly retaliation. Dialogue with civil society, labour, transporters, and consumer groups is equally important.

• Any future policy change touching on retail fuels needs to have built-in measures to help cushion any price spikes in public transport and essential goods, without reverting to open-ended subsidies. One option could be a one-time, non-cash fuel credit for registered public transport operators, pensioners, or civil servants, using verifiable, digital, and non-transferable identities. If well managed, such could show true consideration for hardship and reduce poverty and inflation—examples like Brazil’s targeted welfare for school attendance and medicine for women remain instructive.

• The government could also directly apply any inflows from any future crude or refined petroleum import tariffs or enhanced charges for DSO defaulters to an independently managed capital fund accessible to willing feedstock suppliers or refineries, demonstrating transparency and focusing resources where needed.

• Given that Nigerian energy policy affects both public revenues and poverty, the country may want to consider an online citizen participation platform to monitor critical policies, import levels, revenues, volumes, and prices, taking advantage of the widespread mobile phone usage.

Nigeria’s energy realities demand cautious, sensitive, and adaptive policies. Balancing both upstream and downstream objectives, and weighing fiscal and trade factors, is essential to support all players in the energy spectrum and sustain economic reform.

The challenge is to achieve long-term growth without risk of unraveling.

Dr. Dozie Arinze is an energy policy expert, industry veteran, and entrepreneur.