As Africa pushes toward universal electrification, conversations around access are shifting from infrastructure to impact. The World Bank’s Mission 300 initiative, which aims to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030, highlights both the scale of ambition and the urgency for local innovation.

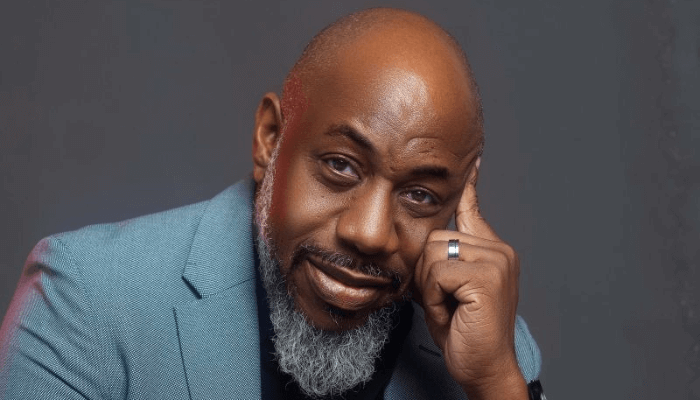

In this exclusive interview with BusinessDay, Olamide Opadiran, Managing Partner at RenCom, discusses why communities must be co-owners of their energy future, how Nigeria’s decentralised renewable energy strategy is redefining productivity, and what it will take to transform passion into a commercially sustainable clean-energy industry. Abubakar Ibrahim brings excerpts:

The World Bank’s Mission 300 initiative aims to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030, an ambitious target that depends on local execution. What do you think needs to change in how large-scale energy programmes are designed and delivered at the community level?

For me, success in electrification isn’t about counting connections; it’s about changing lives. While large-scale programmes like Mission 300 are essential, we must ensure that energy access is not approached as a numbers game instead of a development strategy. What really needs to change is how we think about it. Communities shouldn’t just be recipients of infrastructure; they should be co-owners and co-designers of their own energy systems.

At RenCom, our approach begins with productive use of energy, not just supply. We study the economic rhythm of a community, how people live, work, and trade, and then design solutions that power those daily realities. While lighting homes is essential, the real multiplier effect comes from powering livelihoods. A cold room for fishmongers or a solar-powered agro-mill sustains incomes and communities alike. And when livelihoods thrive, households are illuminated in every sense.

This mirrors what Nigeria’s Decentralised Renewable Energy Strategy (DARES) is doing, anchoring access around productivity. Policies like this, when tied to programmes such as Mission 300, can ensure the billions committed globally translate into measurable economic outcomes locally. The shift I’d love to see globally is simple: stop designing energy systems for people, and start designing with them.

Many young innovators enter the renewable-energy space with passion but struggle with long-term viability. How can Africa move from enthusiasm to building a clean-energy economy that endures and scales sustainably?

Passion builds the first prototype, but systems build the future. The renewable energy space in Africa has no shortage of passionate innovators. What’s often missing is the bridge between innovation and scale: effective structures that make clean energy commercially sustainable, not just socially desirable.

For a sustainable clean energy economy, we need three enablers. First, patient capital that matches our reality. The traditional funding cycle expects quick returns, but in our markets, we’re building entire ecosystems from scratch, including distribution, skills, and even consumer trust. The J-curve is longer here, so the capital must be equally patient.

Second, policy consistency. Nigeria’s renewable sector has seen good progress with NERC’s mini-grid regulation, DARES, and the Energy Transition Plan being clear examples. However, continuity matters. Investors and local developers need predictable policy horizons to plan and execute with confidence.

Finally, we must professionalise local operators. It’s not enough to have innovative ideas. We must build solid governance, transparent reporting, and credible performance data that assures sustainable implementation of these ideas. That’s how we earn the trust of both financiers and communities. When you combine passion with structure, the result is not a project; it’s an industry.

Energy access is often framed around households, yet productive use, powering schools, farms, and small businesses, is what transforms local economies. How does RenCom approach this broader vision of impact?

I’ve always believed that energy is not the goal; it’s the enabler. When we enter a community, our first question isn’t “How many homes can we connect to?” but “What livelihoods can we unlock?” That’s what we call our community-first engineering model.

We design energy systems around the businesses and services that create the most local value. This could include agro-processing centres, cold rooms, welding shops, clinics, and schools. These are what sustain communities economically. Once those anchors are powered, household access becomes viable and sustainable.

This aligns perfectly with Nigeria’s Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Policy (NREEEP) and the Energy Transition Plan (ETP), both of which emphasise clean energy as a pathway to industrialisation and inclusive growth. For me, success means that a farmer in Jos can process her produce locally, a clinic in Borno can stay open 24/7, and a school in Kano can run computers all powered by renewables. That’s how energy becomes development.

Digital transformation is reshaping how energy is generated, monitored, and distributed. How do you see technology, from data analytics to smart grids, changing what’s possible in rural electrification?

Technology has quietly become the backbone of modern energy. What excites me most is how data and digital tools make reliability measurable and predictable. That kind of predictive maintenance not only improves service but also lowers operational costs.

Digitalisation also transforms financing. When you have verifiable usage and revenue data, you can attract new forms of receivable-backed financing, where lenders invest based on performance, not projections. It builds confidence across the value chain.

That said, technology must remain human-centred. Too many solutions assume perfect internet or advanced digital literacy. For us, innovation means designing systems that can function in low-connectivity environments, where operators may be using 2G phones. The real breakthrough will come when technology quietly works in the background, making power more reliable, affordable, and invisible in its complexity. That’s when electrification truly becomes sustainable.

Local manufacturing and supply chains remain key bottlenecks for renewable projects across the continent. What strategies do you think could strengthen local capacity and reduce reliance on imported components?

This is one of the biggest structural challenges in the African energy landscape. Today, a large percentage of components, panels, batteries, and inverters are imported, and that exposes us to exchange-rate volatility and logistical risks. The long-term solution is to develop local manufacturing ecosystems that can supply and service the renewable energy market sustainably.

For Nigeria, the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Policy (NREEEP) and the Nigeria-First Policy recently discussed at the 2025 Nigeria Renewable Energy Innovation Forum are important steps. They emphasise local content and technology transfer, two pillars we should double down on. I see three practical levers to build local strength. First, to incentivise assembly and light manufacturing hubs through tax credits or import duty waivers on components destined for local production. Secondly, to develop supplier certification programmes to ensure quality standards and safety across the value chain. And lastly, to invest in technical training, especially for women and youth, to grow the skilled workforce needed for maintenance, installation, and production.

When we localise as little as 30 percent of our supply chain, we not only reduce costs but also build ecosystem resilience and create jobs. That’s how clean energy becomes both a climate solution and an industrial one.

Recent energy reforms in Nigeria are opening new opportunities for states and private players. How can regulation better support innovation while ensuring affordability and fairness for end users?

The recent reforms, particularly the constitutional amendment allowing states to generate and distribute power, have been transformative. For the first time, subnational governments can directly shape their energy future. That’s huge, but to make it work, regulation has to be a balance of innovation and protection.

I believe tariff flexibility is key. Mini-grid developers and state utilities need room to design cost-reflective tariffs that still remain affordable for consumers. The NERC Mini-Grid Regulation already provides this, but enforcement and predictability are where we must improve.

Secondly, streamlined permitting and licensing would make a big difference. Developers spend months navigating bureaucracy that adds no real value. States should adopt one-stop approval models, like those used in the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP), where all documentation flows through a single digital platform.

Finally, affordability can’t be legislated; it has to be engineered. Productive-use models, community co-ownership, and embedded microfinance all help customers pay sustainably. Regulation should reward those innovations, not stifle them.

Many global climate and energy funds have been launched in recent years, yet local startups often say access remains limited. What practical changes in financing would make the biggest difference for companies like yours?

Access to capital remains one of our biggest constraints, not because money isn’t available, but because it’s structured for a different reality. Most climate finance is designed for large-scale developers, not small or mid-sized operators serving rural markets. We need a fit-for-context financing model.

First, local currency financing. Exchange-rate volatility has wiped out more renewable projects than technical failure ever did. A naira-based credit facility, structured and scaled beyond pilot levels, would unlock confidence and reduce exposure to forex shocks.

Second, enhanced due diligence. Smaller developers shouldn’t face the same complex due diligence as multi-million-dollar IPPs. A lighter initial screening followed by a deeper assessment for shortlisted firms will save time and resources.

Last, embedded technical assistance. Some of the most effective financing programmes are those that pair capital with in-house advisory support. It’s not just about disbursing funds; it’s about strengthening systems and making projects bankable.

At the end of the day, financing must blend capital with local knowledge. That’s how we make climate finance flow to the last mile where it’s needed most.

Sustainability today goes beyond carbon metrics to include community ownership and long-term resilience. How do you define sustainability within the context of RenCom’s work?

For us, sustainability is not a line item; it’s a philosophy. It means designing systems that outlive donor cycles, management teams, and political changes. At RenCom, sustainability has three dimensions: economic, operational, and social.

Economically, we design for productivity. Energy must generate income, not just consumption. Operationally, we focus on local ownership and maintenance. Every project we plan includes community-based technicians and training programmes, because a system is only as sustainable as the people who can fix it.

Socially, it’s about dignity. Electrification should create opportunity, not dependency. When women entrepreneurs run solar-powered businesses or schools extend learning hours, that’s sustainability at work. It’s not about how long the lights stay on; it’s about what happens while they do.

Our guiding principle is simple: if it needs a donor forever, it’s not sustainable. If it powers livelihoods, it will sustain itself.

Off-grid and mini-grid systems are transforming access but still operate somewhat parallel to national infrastructure. What would a truly connected, inclusive energy ecosystem look like for Nigeria or Africa as a whole?

A truly inclusive energy ecosystem is one where off-grid and on-grid systems complement each other, not compete. Mini grids should be built to national standards so they can integrate into the grid when it arrives. That’s how we avoid stranded assets and wasted investments.

Nigeria’s Mini-Grid Regulation and Distributed Generation frameworks already provide for interconnection. The next step is active implementation, creating aggregation platforms that allow distributed assets to feed power back into the grid and earn revenue for communities.

For me, the future is hybrid. Picture a Nigeria where rural communities generate 30 percent of their own power through decentralised renewables, feeding excess back to urban centres. Where a smart national grid balances demand dynamically across states. That’s not fantasy; it’s what a connected Africa looks like.

When we talk about inclusion, we’re not just talking about access to electricity. We’re talking about access to opportunity, productivity, and participation in the clean-energy economy.

Looking toward 2030, what will define real success for Africa’s renewable-energy movement, and what role do you envision RenCom playing in shaping that future?

Success in 2030 won’t just look like 300 million people with light bulbs; it’ll look like 300 million people with possibilities. I see a Nigeria where local factories compete globally because they finally have reliable power; where youth in Kano code for companies in California because they’re connected; where farmers in Jos process and export because they have cold chains.

At RenCom, our role is to be the integrator, translating global policy and capital into dependable local systems. We aim to build, operate, train, and hand over commercially sustainable energy models that grow communities from within. If Mission 300 succeeds, it should ultimately be measured not just in megawatts but in improved incomes, reduced post-harvest losses, and career paths for young technicians.

I believe Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan and the national target to double renewable energy’s share in the mix by 2030 are within reach, but only if implementation is grounded locally. That’s where companies like ours fit in: turning ambition into action and projects into prosperity.

Ultimately, Nigeria doesn’t need sympathy; it needs systems. Africa doesn’t need aid; it needs agency. What we’re building isn’t just a company; it’s a contribution to the kind of country we want our children to inherit. And that, for me, is the real definition of success.