1. No to Fintech Regulatory Commission

Good People, Nigeria wants to establish another commission, and this time, it is a Fintech Regulatory Commission (FRC). The House of Representatives has passed the Bill for an Act through its second reading. But I am not excited. For the size and structure of our economy, we do not need another commission; we need efficiency in the ones we already have.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have the capacity, if properly empowered, to provide the necessary oversight for the fintech space. A new bureaucracy will not solve the problems in the fintech space. Yes, the miracle will not come from a new office with a logo and commissioners; it will come when the existing institutions are funded, retooled and modernised to match the speed and creativity of our innovators.

Mr President, if this Bill finds its way to your desk, please do not sign. Nigeria does not need more commissions. Nigeria needs to support the existing institutions. SEC has the capacity. CBN has the capacity. To do whatever this FRC is created to do https://lnkd.in/eiiMYGsK

Prof Ndubuisi Ekekwe. Visible to anyone on or off LinkedIn

On Soyinka’s US visa, it is what it is

Dr Victor Oladokun •

Nigeria’s Nobel Laureate, revered Prof. Wole Soyinka, whom I hold in the highest regard, has been in the news recently, but not necessarily for the most positive reasons.

Recently, he announced that the US Embassy in Nigeria had invited him to bring his passport for a visa revocation. This followed a 2016 protest in which he ripped up his US residency permit.

Since the news broke this week, a media firestorm has ensued.

Many have turned the incident into a larger-than-life spectacle.

However, the fact remains that our esteemed Bard and Nobel Laureate was fully aware of the potential consequences when he tore up his Green Card nine years ago.

For those in Nigeria upset over the U.S. State Department’s decision, a simple question is this: if a foreigner had done something similar as a protest against Nigeria, would they still be met with the same reaction if the roles were reversed? I believe not.

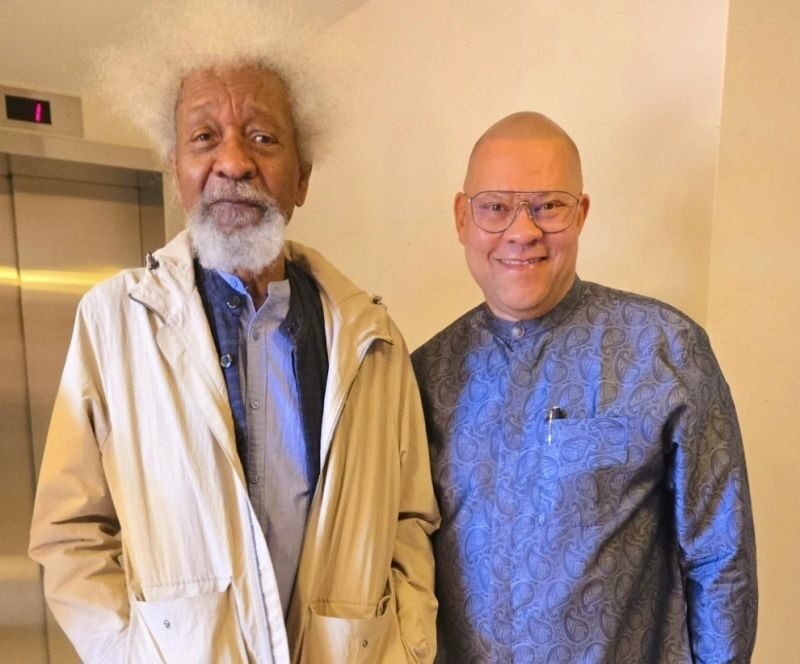

It is also worth noting that since 2016, Prof. Soyinka has visited the United States several times. Last year, I had the honour and privilege to be on a panel with him at Harvard University. As always, he was at his eloquent best. An incomparable African treasure!

Ultimately, regarding this visa controversy and the State Department’s decision, as the saying goes, it is what it is.

Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka announced that the United States has revoked his visa. Soyinka believes the decision is linked to his past criticism of former President Donald Trump, including a recent comparison to the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin.

The 91-year-old playwright is the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

A letter from the U.S. Consulate in Lagos stated the visa was revoked because “additional information became available after the visa was issued.

Soyinka believes it is probably a response to his political critique, particularly his recent remark that Donald Trump is the “white version of Idi Amin.”

Soyinka expressed satisfaction with the revocation, saying he has no desire to visit the U.S. He described the revocation letter as a “rather curious love letter” and stated, “I have no visa. I am banned, obviously, from the United States.”

Bokku Mart Faces Ethnic Prejudice Backlash

Bokku Mart, a Nigerian retail chain, recently faced significant backlash and calls for a boycott over an advertisement that was widely condemned for promoting ethnic prejudice against the Igbo people.

What Happened in the Advertisement?

The controversy stemmed from a now-deleted video posted by Bokku Mart around October 28, 2025, featuring an influencer named Defolah. While comparing the store’s prices to those in open-air markets, she made the following remarks that sparked widespread outrage:

• She stated, “So you mean I can get beans and garri Ijebu at Bokku without any Omo Igbo cheating me?”.

• She added, “It’s so relaxing to shop without someone pulling you from the left and right, shouting my colour.”

The term “Omo Igbo” refers to a person of Igbo ethnicity. The comments were perceived as labelling the entire Igbo community as cheats and disrespecting their dignity.

Public Backlash and Official Response

The advertisement immediately triggered a strong reaction on social media and from public figures.

• Public Outrage and Calls for Boycott: Many Nigerians, particularly from the Igbo community (referred to as Ndigbo), expressed anger and called for a total boycott of Bokku Mart. They demanded that the company take full responsibility for the offensive content.

• Political Figure Weighs In: Denge Josef Onoh, President Bola Tinubu’s spokesman in the South-East, demanded a “full-scale apology” from Bokku Mart to the Igbo ethnic group.

• Influencer’s Apology: The influencer, Defolah, issued a public apology on social media, stating, “It was never my intention to promote any form of tribal bias or disrespect to the Igbo people”. Despite her apology, many found it insufficient to quell the anger.

The key issue is that while the influencer apologised, Bokku Mart itself has not, as of October 29, 2025, issued a formal or direct public apology for the advertisement, which is a central demand of those calling for the boycott.

The Ad That Exposed Nigeria’s Dark Obsession with Tribe

By Tosin Adeoti

When Bokku Mart posted that ad, the one where the influencer smiled into the camera and joked about shopping “without any Omo Igbo cheating me”, it was a mirror held up to a country that has grown too comfortable with prejudice.

People were rightly outraged. Of course, the influencer apologised and Bokku Mart deleted the video. But the damage had already been done. The slur had slipped out not as a slip of the tongue but as a reflection of a mindset that had passed through layers of approval. From the influencer’s script to the marketing team to the senior management to the brand’s social media managers.

Nobody thought it was wrong.

That, right there, is the problem.

The real question is not why a brand said something offensive. It’s why everyone along the chain of approval thought it was fine to say it.

Because this didn’t happen in a vacuum.

We got here the moment bigotry became normalised from the top. It began when public figures, people elected or appointed to represent millions, could publicly speak ethnic hate and suffer no consequences.

In 2019, Senator Remi Tinubu, now First Lady, was captured on video saying what many found deeply offensive. She told a crowd that Igbos were “ungrateful” and that Yoruba people would “overcome them and inherit their properties in Lagos.”

Not long after, in 2023, Bayo Onanuga, a senior media aide to Bola Tinubu’s campaign, doubled down on similar rhetoric. “I am first a Yoruba before being Nigerian,” he tweeted, insisting that the Igbos were an “existential threat” to the Yoruba people. When criticised, he refused to apologise.

And what happened when these two statements were? Nothing. No sanctions. No reprimand. No symbolic disapproval from those in power. The comments were treated as political talk, something to move on from.

But here’s the thing about leadership: it doesn’t just manage policy, it shapes culture. When leaders cross moral lines without consequence, they redraw those lines for everyone else. Or were we not around in 2023 during the elections when ethnic bigotry was fuelled by the political class to incite and disincentivize voting?

So, that’s how a slur like “Omo Igbo” ended up in a supermarket advert in 2025. The people approving that ad were not monsters. They were ordinary Nigerians. But in a society where prejudice has become part of casual conversation, bigotry begins to sound like marketing creativity.

Once you normalise hate in politics, it trickles down into pop culture and eventually into everyday interactions.

Suddenly, jokes about “Igbos cheating” or “Yoruba laziness” or “Hausa backwardness” start to sound harmless, even funny. Until one day, someone uses them to justify exclusion or violence.

This is not unique to any particular tribe. Every group in Nigeria harbours its share of prejudice. However, there is a difference between what people say privately among friends and what society permits to be said publicly with approval.q

That difference is what separates civility from chaos.

Nigeria has walked this path before. In the 1960s, political rhetoric drenched in ethnic suspicion helped ignite the crisis that led to civil war. Look into the archives and you’d be shocked to see newspapers carrying headlines about “Igbo domination” in the North and “Yoruba betrayal” in the East. Words became fuel, and soon, fuel became fire. By 1967, the nation was burning.

Fifty years later, we like to think we have outgrown such divisions. However, the truth is that we have only learned to dress them up.

Our social media has become the new marketplace of prejudice — hashtags replacing war songs, tweets replacing pamphlets. Tribal baiting now hides behind jokes and memes. The tone is lighter, but the poison is the same.

After the Bokku ad went viral, the reaction split the internet. On one hand were Nigerians, across ethnic lines, condemning the video as wrong and divisive. On the other hand, came the defenders, primarily supporters of the current government, who felt their “own” were under attack.

“Support Bokku Mart,” some tweeted. “The Jews support Jewish businesses. The Arabs support Arabs. We must defend ours.”

Overnight, the boycott became free publicity. From what I read, Bokku Mart gained thousands of followers. Shoppers queued for its bread and groceries. The slur that should have humbled a brand ended up boosting its visibility.

It’s an irony that says a lot about who we are becoming: a people more loyal to their tribe than to the truth.

The difference between a civil society and a dangerous one lies in how it reacts to its own ugliness. Mature democracies understand this, which is why public figures who make racist or bigoted remarks are expected to resign or apologise. This is not necessarily because everyone believes in their sincerity, but because the act itself reaffirms a moral boundary.

Those rituals matter. They remind society that certain things are never acceptable, no matter who says them.

Nigeria desperately needs that line again.

When brands like Bokku cross boundaries or when politicians erase them, it falls to ordinary citizens like us to redraw them. To insist that we can disagree politically or culturally without resorting to ethnic hatred.

The actual test of Nigeria’s unity is not in singing the anthem together during Super Eagles matches or flying the same flag during Independence Day celebrations. It is in whether we can resist the temptation to dehumanise one another in moments of anger.

The Bokku case should never have happened, but now that it has, it must serve as a national reminder that bigotry is not culture. It is cowardice disguised as pride.

And no matter how many followers it wins on social media, it will always make the country poorer.

Because a nation cannot prosper when its people see each other as enemies.