In June 2025, Nigeria’s National Assembly approved a second extension of the capital component of the 2024 national budget—pushing its implementation deadline to December 31, 2025. Relatedly, this development has further consolidated the government’s culture of running multiple budgets in a single fiscal year since the culture started in the 2023/2024 budget cycle. The move, while legally permissible under the Appropriation Act and Finance Act provisions, has reignited debate over whether such rollovers reflect policy continuity or expose a systemic execution gap.

The National Assembly’s rationale was clear: allow ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) to complete ongoing capital projects and avoid wasteful abandonment. Yet, critics argue that this repeated rollover—from December 2024 to June 2025, and now to year-end—signals weak procurement planning, cash flow constraints, and a credibility crisis in public finance management.

The Budget Office of the Federation defended the overlap, citing global parallels (in India, Kenya, and Indonesia) and the need for institutional flexibility. According to its director general, Nigeria is currently operating three budget instruments simultaneously—the 2024 Main Appropriation Act, a supplementary budget, and the 2025 Appropriation Act. While this may sound chaotic, it’s framed as a transitional system aimed at reconciling planning cycles with execution realities.

Still, lawmakers like Senator Abdul Ningi and Senator Seriake Dickson have called for deeper scrutiny. They question whether the extension is backed by actual revenue shortfalls or simply masks governance distractions and political preoccupations.

In essence, while the budget rollover mechanism is legally sound, its repeated use raises important questions: Are we witnessing a maturing fiscal system adapting to real-world constraints—or a loophole culture that erodes transparency and accountability?

2024 budget of ‘Renewed Hope’

On November 9, 2023, PBAT submitted an appropriation bill of N27.5 tn for the 2024 fiscal year before the National Assembly, which was subsequently reviewed and passed by the chambers and eventually signed into law on 1st January, 2024. The budget was increased by an aggregate of N1.27 tn by the National Assembly to N28.78 tn.

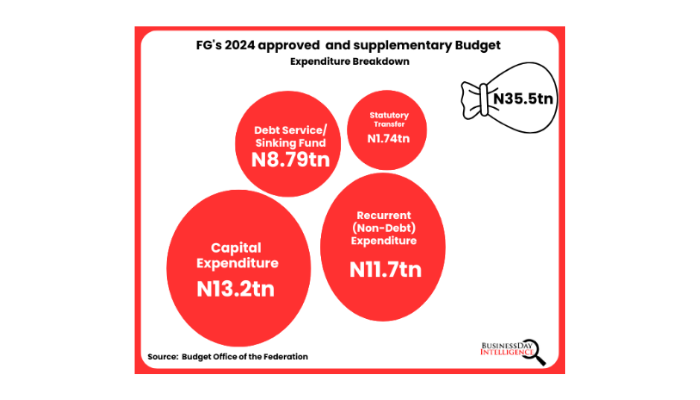

By June 2024, the President sent a request to the National Assembly for an amendment to the Appropriation and Finance Act by increasing the budget by N6.2tn, eventually pushing the initial and supplementary budgets to N35.5tn.

A more disaggregated look at the budget revealed that ₦13.2 tn, or 34.75 percent of the budget, has been set aside for capital expenditure; ₦11.7 tn, or 30.47 percent of the total budget, has been set aside for recurrent expenses; and ₦8.79 tn has been set aside for debt servicing/sinking fund. The remaining N1.74tn has been earmarked for statutory transfers.

Read also: Senate extends 2024 budget till December

Capital budget rollover: Between growth imperatives and governance gaps

Achieving inclusive prosperity and sustained economic growth in Nigeria undeniably requires higher public investment. Historically, Nigeria has ranked among the lowest globally in public spending. Between 2015 and 2024, total government expenditure averaged just 13.1 percent of GDP—well below the global average of 30 percent and Sub-Saharan Africa’s 21.2 percent. This chronic underinvestment continues to stifle human capital development, infrastructure delivery, and economic diversification.

However, the recent extension of the 2024 capital budget, which is the second such rollover in two years, raises concerns about the credibility and clarity of Nigeria’s fiscal management. Budget overlaps, now commonplace under the Tinubu administration, have created execution bottlenecks, delayed payments to contractors, and blurred lines of accountability. Ministries and agencies are now caught navigating two concurrent budgets, complicating disbursement tracking and impact assessment.

While constitutional reforms were proposed to limit excessive delays and curb recurrent supplementary budgets, the Senate’s passage of Bill S.854 extending capital spending into December 2025 may have set that momentum back.

Ultimately, the issue goes beyond legal compliance. It speaks to a deeper governance challenge: without urgent reforms to restore budget discipline, enforce transparency, and align spending with outcomes, the promise of public investment as a catalyst for growth risks being lost in translation.

Stability, stimulus and strain

The extension carries mixed economic implications. On one hand, the rollover allows the government to continue capital projects without fresh legislative bottlenecks. This could stabilise infrastructure development and ensure continuity, particularly for road, rail, and power projects already underway. However, Nigeria’s capital budget performance historically averages below 70 percent, and this rollover may mask inefficiencies rather than correct them.

On the downside, extended spending within the same appropriation cycle may heighten inflationary pressures—still above 20 percent as of May 2025—by injecting more money into an economy grappling with supply chain constraints. Coupled with a debt service burden consuming over 65 percent of revenue, prolonged disbursements could deepen fiscal stress and delay project completion timelines, frustrating citizens and contractors.

Private sector confidence may also waver. Investors rely on predictable fiscal cycles; the current move, while legal, raises questions about governance discipline. There are growing fears of procurement loopholes, duplicated line items, and weak oversight. The National Assembly and institutions like the Auditor-General’s office must intensify scrutiny to ensure transparency and value-for-money. Without this, the rollover could be perceived not as a tool of stimulus, but as a sign of fiscal strain and policy uncertainty.

Read also: Senate approves N1.8tn budget for FCT

Governance and transparency questions

The move has also reignited concerns about Nigeria’s persistent governance and transparency challenges. Key among these is the risk of procurement bottlenecks and weak oversight, which have historically plagued budget implementation. With the extension, fears of duplicated projects and inflated costs are intensifying, especially in sectors like roads and power where large contracts dominate. Questions also linger around fiscal indiscipline—delays in project execution, abandoned works, and the recycling of unspent funds without proper justification.

The National Assembly, though constitutionally mandated to approve and monitor appropriations, must rise above rubber-stamp tendencies and exercise robust oversight. Similarly, audit institutions like the Office of the Auditor-General must provide timely performance audits and flag irregularities in procurement and contract execution. Without such checks, the rollover risks becoming a political instrument for unchecked spending rather than a tool for strategic continuity and economic impact. Stronger transparency mechanisms are essential to restore public trust.

The way forward

This new culture of budget extensions signals persistent weaknesses in budgetary execution, undermining fiscal discipline as well as business and investor confidence. Dr Chinyere Almona of LCCI notes that while project completion is a laudable goal, serial rollovers erode budget credibility and fail to guarantee disbursements, with 2024’s capital budget deemed “effectively unfunded” after accounting for N14.3 trillion in debt service and N13.6 trillion in recurrent costs. Muda Yusuf of CPPE attributes this to unrealistic revenue assumptions, like 2024’s oil revenue shortfall, and overambitious budgets.

To reform, enforcing the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) is crucial for aligning projects with funding capacity. Tunde Abidoye of FBNQuest highlights administrative bottlenecks as a key issue. Institutionalising performance-based budgeting, prioritising executable projects, and streamlining processes will enhance economic resilience, ensure sustainable execution, and secure funding for near-completion infrastructure, as advised by LCCI, tying fresh borrowing to named assets for accountability.