In a space of four years, Nigerians and their friends have witnessed twice a perfect re-enactment of Great Expectation orchestrated by their president who, it seems, has the penchant for creating prolonged suspense before selecting ministers that form his cabinet.

The story of Great Expectation as recorded by Charles Dickens, a celebrated English novelist, is that of reversal in expectation, dashed dreams and disappointment, all culminating in despair and frustration.

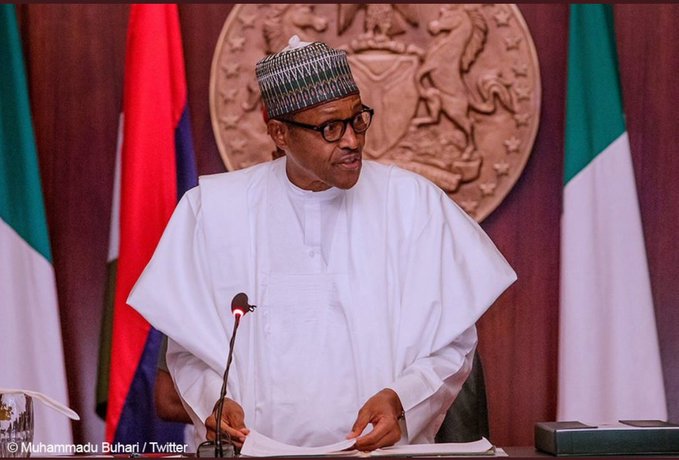

In his first term in office, President Muhammad Buhari spent whole six months looking for saints and men without blemish who would work with him as ministers. That raised hopes and expectations among Nigerians who thought that those saints would be the messiah Nigeria had been waiting for.

When eventually the president unveiled his list of saints and would-be drivers of the change mantra that gave him victory at the polls, it was not only a rude shock, but also a testament to Nigerians that, truly, perception is different from reality. The list was not just that of regular, ordinary Nigerians, it was also a reflection of the thinking that went into their selection.

That was Great Expectation Part 1. The second part of the story is still playing out. In February this year, fate smiled on the president and he emerged the winner of the presidential elections held that month, although the result is still being contested at the tribunal. Nigerians thought some lessons had been learnt from the heavy price both the country and its economy had to pay for the long delay in setting up the cabinet in the president’s first term.

But they missed it. It was another Great Expectation up to the president’s inauguration three months after election. The explanation by the president and his managers was that he was looking for extra-ordinary men and women that would do extra-ordinary things in line with his Next Level agenda.

Eventually, four months after winning election in a country that is hungry and in dire security situation, the president unveiled his list of ministers that kept many lips agape, wondering whether they were in fool’s paradise or theatre of the absurd. It was another reversal in expectation and shattered dreams.

But the list has come to stay and those selected, 43 in all, among them seven woman, have been screened. They have all been cleared. Nigeria is a country ruled by hope and so, its people are always hopeful. This is because they are used to long suffering which, according to the Christian Holy Book, is a fruit of the spirit and the only virtue that oils suffering.

Against all expectation that the minister-nominees, who were screened without any portfolio affixed to them, would be inaugurated as soon as the Senate ritual was over, the President again shifted the goal post, announcing that the swearing in ceremony will hold on August 21.

The announcement was followed with criticism as Nigerians wondered “what’s in appointment of ministers?” Abuja appears to be glamourising what is regarded as inconsequential in most countries of the world. An analyst, who spoke with BDSUNDAY on condition of anonymity, said: “It appears that appointment of ministers in Nigeria in this dispensation has become a rocket science.”

Much hope is therefore, tied around Buhari’s ministers as many Nigerians believe that a lot of things have gone wrong, needing to be fixed. But the very discerning citizens, those who reason beyond pecuniary interests and clannish considerations, sincerely believe that these ministers must be magicians to drive the speedy change and the ‘Next Level’ flight to the Promised Land.

About 12 of the new ministers are returnees from Buhari’s first term and many analysts converge on the understanding that whatever that was responsible for their below-par performance could also hamper their input this time around, especially, as there has been no indication that the impediments have been removed.

Obviously, there were impediments to effective performance of Buhari’s ministers in his first term in office. These impediments included a rigid and inept leadership, macro-economic challenges, mundane issues such as lack of political will, and placing ethnic and religious considerations above national interest.

Admittedly, the Buhari government inherited a very weak and fragile economy but failed, contrary to their electoral promises, to do something about it. The action and inaction of government, which compelled some foreign investors to leave the country, hastened the slip of the economy into recession.

The attendant hyper inflation, low industrial productivity, loss of jobs and crimped consumer purchasing power all combined to cripple both the economy and governance. This was made worse by what became a ‘third force’ in government-the president’s body language-which made it difficult for anybody, including the ministers, to do or say what could be done to salvage the situation.

It was such that when the economy eventually crawled out of the 15-month recession in the second quarter of 2017, economists contended that it was not because of any known action of government, but those of private sector operators, especially those in the manufacturing and services industries.

The leadership was so inept that rather than think of how to create an enabling environment that would create economic activities, it was busy chasing stolen money. How much that has helped the economy remains a matter for the imagination. Because of these and a lot more, most of the ministers were just spectators and the very few whose ministries were pivotal to the economy and governance were operating at “half installed capacity”.

Some of the ministers who had record of good performance like the minister of Power, Works and Housing, Babatunde Fashola, struggled to prove their mettle. Fashola was saddled with three key ministries because of his superlative performance as governor of Lagos State from 2007 to 2015.

Though it is said that he did well in both power and works, the housing ministry under Fashola had never had it so poor. It is a popular belief, especially among private sector operators, that the government shouldn’t have any business in direct housing production but provide the enabling environment for private investors to do so.

But Fashola appeared so overwhelmed that even his brilliant national housing roadmap remains a day-dream till today. The roadmap, which focused on home seekers who are in the majority and those who are most vulnerable, placed much premium on planning which, the government reasoned, was key to successful execution, requiring a clear understanding of those who houses were to be provided for.

Fashola insisted that government must lead the change that was needed in the housing sector, recalling that, over the years, Nigeria had embarked on a series of housing initiatives but not one of them had been pursued with consistency or any measurable sustainability.

“We are convinced that this change must be led by government and subsequently driven by the private sector”, he said, citing the public housing initiative of the United Kingdom which was started by government in 1918 and, as of 2014, it had recorded 64.8 percent of the people who were home owners.

He also cited Singaporean initiative in housing which, he added, was started by government in 1960 and has provided housing for 80 percent of its people, pointing out that what was common to both models was that there was a uniformity of design, a common target to house working class people, and not the elite; standardisation of fittings like doors, windows, space, electrical and mechanical, and also a common concept of neighborhood.

As lofty as this idea was, it was never followed through and housing sector analysts blamed it on the interplay of a tottering economy and a socialist government that did not believe in the power of private capital to catalyse economic growth and development.

Both the ruling party, All Progressives Congress (APC) and President Buhari have promised Nigerians that they will be taking both the country and its economy to the Next Level which, by skewed and conservative interpretation, means the ‘Promised Land’.

But it remains to be seen how the Next Level agenda is to be realised when all the impediments, as aforementioned, are still intact. Though analysts say the economy has recovered and even grown, that still remains a theoretical construct, because the impact of the growth is yet to cascade to the homes of average Nigerians.

Furthermore, investment interest and investor-confidence are still edgy. The government is yet to give clear signal to investors that it is ready to do business. Government policy on key sectors of the economy remains foggy and does not give investors, foreign and local, enough comfort to move cash into Nigeria markets.

Another major impediment on the way to the Next Level is the security situation in the country. Deliberately, government has decided to concentrate the management of the entire country’s security architecture in the hands of people from one section of the country where, incidentally, the greatest threat to the country’s stability emanates from.

In light of the above, Nigerians are concerned that the next four years, in spite of the ministers, may not be different from what they have seen in the last four years of Buhari and APC. The ministers need an enabling environment for their role in government to be seen and felt.

Government has to be less rigid; it has to be less-intolerant; a lot friendly and accommodating enough to open its doors to private capital to come into the country and thrive. The government has to be more proactive than reactive. It has to start thinking out of the box because it is only then that the stuff of which the ministers are made will start manifesting in their respective ministries for a common goal.

CHUKA UROKO