The first time Babatunde Adebayo wittingly exercised his franchise, 27 February 1999, he was a 31-year-old man laying his hands on what he could to secure his future.

Then, Olusegun Obasanjo the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) flag bearer was in a cut-throat race with Alliance for Democracy’s (AD) Olu Falae for the presidential seat.

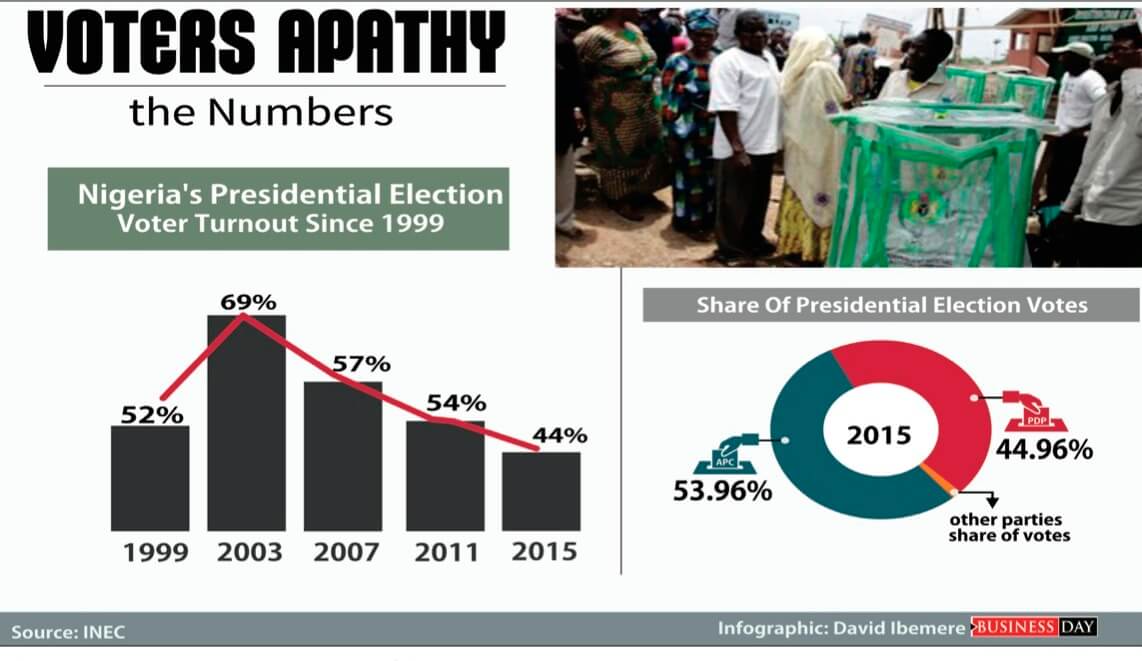

The election which retains its standing as one of the most-participated polls garnered 30,280,052 votes in its entirety, bringing voters turnout to 52.3 percent.

Before riding to power on the back of 18,738,154 votes, Obasanjo at a party convention in the city of Jos made it clear in his acceptance speech as the presidential nominee, that Nigeria had no business with poverty.

That with the vast potential in human and material resources, his administration would strive to eradicate poverty. ‚ÄúNigerians should in the next four years, be assured of, of least, the basic necessities of life,‚ÄĚ pledged the former president.

But Adebayo had become used to that cliché of promises, even at that time.

Nothing around his vicinity instilled the sense of belonging that he had a government to alleviate his standard of living or one that at least, expressed its commitment in the provision of access to good road networks, stable electricity supply, qualitative education, potable water system and wholesome sanitary conditions to begin with.

With Nigeria‚Äôs GDP at a mere $57.4 billion in 1999, the economy barely expanding, and GDP per capita at $496, his deflated confidence was further exhausted by the scarcity of job opportunities in town. He began clearing his path to London for ‚Äėgreener pastures‚Äô.

As a result, participating in that election was a sheer adventure for him.

He didn’t believe in the potency of that vote, especially as elections in that era was sullied in manipulations and conflicts. He only found it fascinating to join the excitement that brewed while maintaining long queues to cast a vote.

By the next election in 2003, Adebayo was still in town. He simply went for accreditation but did not return to vote.

‚ÄúI didn‚Äôt go back because I was playing scrabble. Yes, I counted that as more important than going back to waste my time,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúThat I have a permanent voter‚Äôs card (PVC) does not mean I have a say in the country. The only thing that counts is my family and I. I will only get my PVC because it‚Äôs my right. I‚Äôll get my tax identification number (TIN), international passport and driver‚Äôs license. Nigeria has a cracked system.‚ÄĚ

Twenty years later, more Nigerians have increasingly become disenchanted in the affairs of the country like Adebayo and that mien is expressed in their indifference to showing up at polling centres.

Perhaps, those in and around the metropolis can point to a thing or two in terms of physical development, most in rural settlements can easily say things have remained the same despite the interrupted experience under democratic dispensations since 1999.

In urban hubs, well-heeled citizens express minor interest in rowdy election, since they command individual economies in which government’s impact is next to nothing.

Of the 67,422,005 registered voters in Nigeria during the last election (2015), only 31,746,490 (47.08 percent) were accredited. Among that were 29,432,083 of votes cast, of which 28,587,564 (97 percent) were valid.

Statistics by the Centre for Public Policy Alternatives (CPPA) show that the election was particularly different from the 2011 edition as it reflected more than ever, a population with enfeebled trust in the process electing its representatives.

Voter turnout significantly dwindled by 25 percent from a total votes of 38,209,978 in 2011 to 28,587,564 in 2015, despite an increase in the voting age population to 87,784,373.

Turnout, derived from the number of registered voters divided by the number of total votes cast was 43.65 percent, marking the lowest in Nigeria’s democratic history since 1999. It moved from 52 percent in 1999 to 69 in 2003, 57 in 2007 and 54 in 2011.

In juxtaposition with the 2011 outcome, turnout for the 2015 presidential election dived in all the geopolitical zones, except in the south-west where it appreciated by approximately eight percent, from 32 percent to 40 percent.

Going by a state by state breakdown, only 13 states had 50 percent or more voter turnout. Almost all the Northern states, including those affected by insurgency had turnout of at least 40 percent, except Borno with 30 percent.

Surprisingly, Lagos, a metropolis considered relatively non-violent in terms of pre or post-election violence, had the lowest turnout at 29 percent. In contrast, Rivers state had the highest turnout at 71 percent amid a slew of controversies around electoral malpractice.

Adebayo’s lack of faith in the system of governance is an issue analysts agree is rooted in the rife belief that votes don’t count and that election outcomes are predetermined by a minority of elite.

Wale Ogunade, a constitutional lawyer and President, Voters Awareness Initiative describes this as the adverse effects of unfulfilled promises. ‚ÄúPeople are tired of empty of politicians in this country,‚ÄĚ Ogunade said. ‚ÄúThey would rather be indifferent than expend effort in futility.‚ÄĚ

Moreover, voters in recent times distance themselves from voting for a pocket of other reasons including the seeming recycling of leaders.

There is a global wave of taste for youthful presidents and Nigerians youths desire same. But with slim chances for their preferred candidates, some rather duck the polls.

Another major factor responsible for voters apathy remain electoral violence since election statistics now hardly go without being marred by death tolls.

With issue-centred campaigning undermined by politicking, and supporters divided along religious, ethnic and sectional bias, over 160 people across the country had lost their lives already to election related violence as at January 2015 (a few months before the last polls).

At least 30 people were killed largely from inter-party conflicts and attacks on election sites, with problems being most pronounced in Rivers and Akwa Ibom states.

There might not be significant changes in the narrative, which will no doubt likely bruise voters turnout in 2019.

The United States Institute of Peace observed in a report dubbed ‚ÄėNigeria‚Äôs 2019 Elections: Change, Continuity and the Risks to Peace,‚Äô that the conflict between farmers and herdsmen within the northern, central, middle-belt states and the apparent failure of government to nip the Boko-Haram insurgency in the bud also strengthens the perception that security remains a challenge.

The case of the missing voters also poses a risk to integrity of the votes cast.

Cases where people register and fail to turn up created huge opportunity for rigging and manipulations before the introduction of biometric card readers, according to Ade Adebambo, an All Progressive Congress (APC) party agent.

When a party with the upper-hand in an area is on the verge of losing an election due to poor turnout, it would begin to mobilise supporters to vote and ensure that the numbers tally in a way that won’t elicit suspicion.

To facilitate that, Adebambo says party agents are either bought to look the other way or threatened to succumb. ‚ÄúIf for instance 2,000 people registered to vote but during the election, they got 200 where they need 500, the incumbent can mobilise people from another area to close the margin. These were things that happened. This time, things have changed.‚ÄĚ

Assuring that containment of manipulations would be further deepened in 2019, Femi Adebiyi, the public relations officer at INEC said the commission will adopt simultaneous accreditation and voting to reduce incidence of low turnout.

The method, he said, was experimented successfully in the recent gubernatorial elections in Anambra, Ekiti, and Osun, although observers believe those elections were characterised by irregularities.

‚ÄúWe understand that this is a machine (card reader) and wherever there is going to be failure, we have back up,‚ÄĚ said Akinbiyi who feels the commission (INEC) is being unfairly hammered by critics. ‚ÄúWe expect that machines will fail. It fails but what is the percentage? If of all the process we have just about five percent failure, people will begin to hold on to that.‚ÄĚ

Going forward, observers appear positive that the 2019 election could be on track for improvement in turnout as enlightenment of voters has increased as to the dangers of leaving voting decisions in incompetent hands.

Through the social media, more youths have been educated about government policies, actions and inactions and ‚Äúwill keep trying their luck because they know how important it is for them to vote,‚ÄĚ according to Chidi Okereke a social media influencer with over 68, 000 followers.

However, the concern for other observers is that while voter turnout may nudge higher, it will be mostly induced by monetary enticement from politicians, casting shadows on the integrity of elections.

That was exemplified in the last election where contending parties dished out money to voters upon proof of voting in their favour.

Balarebe Musa, a former Governor of Kaduna state and National Chairman of the Peoples Redemption Party shares this sentiment and believes turnout may increase, not because of voters‚Äô conviction that the candidates can perform but because they need the monies and hand-outs to be offered. He said: ‚Äúthe fate of the election in Nigeria is decided by money. You can see what happened in the party primaries. This will continue even at the national election, people will be bought to vote because they are so poor,‚ÄĚ he said.

In Nigeria, voting is both a right and obligation once age 18 is attained.

But it has not become compulsory like in 22 other countries mostly in Latin America.

A citizen can face a fine of $20 (N7, 200) for failing to vote in Australia, while eligible voters who duck the polls for three consecutive elections in Brazil may have their voter identity cancelled.

It doesn’t end there. They can be restricted from borrowing from government financial institutions, obtaining a passport or taking public office if approved in a civil service test.

Under compulsory voting, democratic election of leaders is treated as the responsibility of citizens, rather than a constitutional right.

Just like civil responsibilities such as tax payment, voting in these democracies is regarded as one of the obligations to community noted in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

In effect, research says the method appears to have produced governments with more stability, legitimacy and a genuine mandate to govern, a situation which in turn benefits all individuals.

The idea that compulsory voting results in a higher degree of political legitimacy is based on higher voter turnout. Voluntary voting, for instance, prior to 1924 accounted for between 47 percent and 78 percent turnout of eligible voters in Australia. But with the introduction of compulsory federal voting in 1924, this figure soared to between 91 and 96 percent, with only 5 percent of eligible voters accounted as not enrolled.

In contrast, Venezuela and the Netherlands in 1967 shifted from compulsory voting to voluntary participation and turnout in the subsequent national Dutch poll trimmed by about 20 percent while Venezuela saw a drop in attendance of 30 percent in 1993 once compulsion was discarded.

Until something similar happens, ‚ÄúPeople will come out to vote when the dividends of democracy become noticeable; when promises are fulfilled and perhaps when the Lagos-Ibadan expressway, a route that connects the economic nerve of the country to other states is completed,‚ÄĚ said Adebambo, the APC party agent.

Temitayo Ayetoto